Right now, as I’m writing this, its winter in Pittsburgh and the weather is freezing. But here in my office, its a balmy 71 degrees Fahrenheit (or 22 degrees Celsius, as we say in science). A little vent is gently whispering pre-warmed air into the room. The marvelous thing is, the temperature will stay at this comfortable level. A thermostat on the wall lets me choose what temperature I want (well, in theory. Actually, the thermostat is in another room. Facilities Management actually decide what temperature is comfortable, but today they seem to have nailed it).

Its worth taking a moment to remember how a thermostat works. The heating comes from a furnace, heating up air and then blasting it through the vents. Left to its own devices, the room would just get hotter and hotter. But the thermostat contains a thermocouple, which senses the temperature. When it gets past my chosen temperature, it shuts off the blast of hot air and the temperature stops rising. My office stays comfy for a few minutes. But then, because it’s still winter outside, my office begins to cool. Luckily, as soon as it drops just below my set temperature, the thermostat will detect this and kick the heating back on. And there we go – the temperature drifts imperceptibly up and down slightly through the day – but for me, it remains comfortable. And its the same for everyone else in this rather large building. Everyone can go about their jobs rather than shiver distractedly.

So, I’m sure this isn’t news to you. But the basic ideas are repeated in biology – this is how homeostasis works in your body. Think of blood glucose: Eat a meal, blood glucose goes up. The pancreas detects this, and releases insulin. The insulin causes blood glucose to lower. And that reduces the insulin release by the pancreas. And so blood glucose is held in a fairly narrow range.

So now lets take you into the plasma membrane. Right now, the plasma membrane in all of your cells is hard at work. Proteins are opening pores to allow select molecules and ions into and out of cells. Little bubbles of membrane are being pinched off by complex protein scaffolds, swallowing chunks of nutrients and peptides. Yet more membrane bubbles are fusing with the plasma membrane, being pulled together by large protein machineries, releasing their inner cargoes from the cell. And that floppy plasma membrane is being pulled taught and given shape by a closely pinned skeleton of polymerized proteins, known as the cytoskeleton. There are hundreds of types of proteins doing these essential jobs, and they all need something that licenses them to work in the plasma membrane – as opposed to any of the cells’ dozens of internal organelle membranes.

What licenses all these proteins to work there? Our favorite membrane lipid, PIP2

(more precisely, PI(4,5)P2). It is imperative for the cell to maintain enough PIP2 for the plasma membrane to stay functional and the cell to stay alive. So how do cells figure out if they’ve got enough PIP2 in their plasma membrane? What is the homeostatic mechanism?

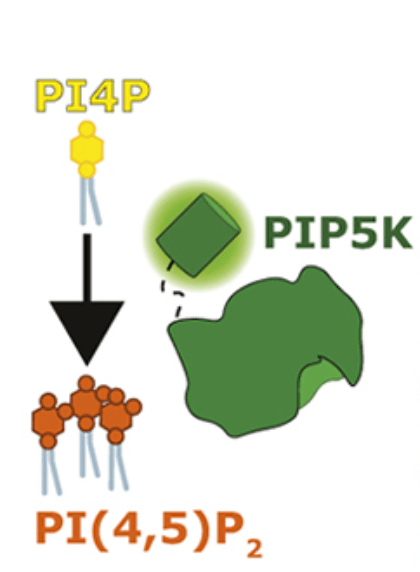

We didn’t know. That was the problem a recent graduate student from the lab, Rachel Wills, was tasked with figuring out. Thinking back to our thermostat analogy, we knew one component: We new the “furnace” part, the part that generates the PIP2. This is an enzyme called PIP5K, and it adds the last phosphate group to a PIP molecule to make PIP2, as you can see right here.

We’ve known the identity of this PIP5K enzyme for nearly four decades. Its a very active enzyme and does a great job of converting PI4P into PIP2. But, like our thermostat, how is it turned off when the cell has enough PIP2? That’s a pretty important question actually, because we know two things: firstly, it doesn’t run out of PI4P “fuel”, because cells maintain plenty of this lipid in their plasma membranes. Secondly, we know of diseases where cells accumulate too much PIP2. This leads to a host of diseases from kidney failure to neurodegeneration.

We figured we would start looking for something that could turn PIP5K off. As so often goes in science, we worked really hard on this for three years, and then somebody else beat us to it. A team in Harvard found an evolutionary cousin of PIP5K, known as PIP4K, can actually inhibit PIP5K and stop it efficiently making PIP2. We tested this, using chemigenetics to force PIP4K onto the membrane by attaching it to FKBP protein, and “sticking” it to a plasma membrane targeted FRB protein using a drug as glue. In this video, you see FKBP-PIP4K (blue) getting stuck to FRB-PM (purple):

What is cool is what happens to the PIP2 in the PM, marked with the orange biosensor protein. See how it gradually decreases in the membrane after we stick PIP4K there? Thats because the cell’s PIP5K is being switched off, and it can’t make PIP2 to maintain the levels in the membrane.

So woo! We know what switches off the furnace. But the important bit is the sensor – that detects the heat in your thermostat, and monitors the PIP2 level in cells. What is doing that? We didn’t know. But we had an idea.

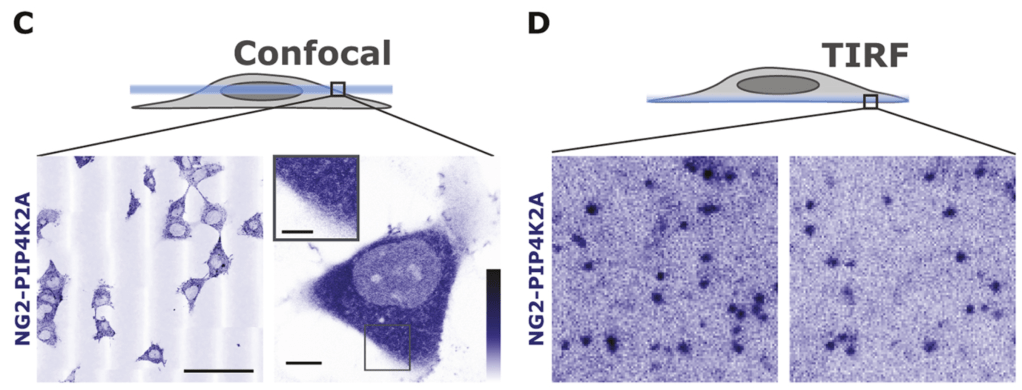

Rachel attached fluorescent protein tags to the PIP4K enzymes. Most of the protein is floating around in the cytoplasm, but if you look carefully at the bottom of the cell, you can see individual fluorescent molecules stuck to the membrane:

What sticks PIP4K to the membrane? We figured if it was PIP2, then PIP4K might be the sensor for the lipid. Indeed, when Rachel depletes PIP2 from the membrane with our chemigenetic trick, look what happens to all those membrane-associated molecules:

They dissappear! So PIP4K sticks to PIP2 in the membrane. In fact, its very sensitive to the PIP2 level. When the levels of PIP2 increases in an artificial membrane, the amount of PIP4K that can bind increases sharply:

Given that we know the PIP4K in the membrane inhibits PIP5K, this sets up a homeostatic feedback loop that controls PIP2 in the membrane:

That’s our lipid homeostat!

Right now, we’re asking some deeper questions about this pathway. Firstly, how does this work exactly? We’re using A.I., directed mutagenesis and some structural biology approaches to understand exactly how PIP4K proteins inhibit PIP5K.

Secondly, we’re asking how messing up this thermostat causes disease. Specifically, which membrane processes are affected, particularly by increased PIP2 levels? We have one striking observation: The cancer driving PI3K pathway, that uses PIP2 as its substrate, depends linearly on the amount of PIP2 in the membrane. So increased PIP2 levels could actually assist in activation of this pathway in cancer.

You can read Rachel’s paper for free, and also the Harvard team’s paper.